There are countless amazing women who changed our country, from activists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Harriet Tubman, to pioneers such as Amelia Earheart and the women of the Mayflower. In this article, however, I want to share the story of just one: Elizabeth Peratrovich, a native Alaskan civil rights leader.

Women’s History Month is a time to celebrate the women who have helped change our country by fighting for liberties like voting rights or racial equality. Many countries celebrate International Women’s Day, but the United States is the only nation that dedicates the entire month to our ladies. This March is the 37th National Women’s History Month, but originally this celebration of incredible women was just one day, March eighth. Starting with Sonoma County, California, in 1978, schools began hosting their own Women’s History celebration on the week of the eighth. The idea quickly caught on and President Carter issued a proclamation that the week of March eighth in 1980 would be National Women’s History Week. More lobbying efforts followed, and in 1987, Congress declared the entire month to be National Women’s History Month.

On February 16, 1945, the United States passed the 1945 Anti-Discrimination Act, the first of its kind in America. One of the key factors in the bill’s success was a woman named Elizabeth Peratrovich, a native Alaskan and member of the Tlingit nation. She tirelessly fought to address the issue of racial discrimination, and her efforts paid off when the 1945 Anti-Discrimination Act was passed.

Born on July 4, 1911, Elizabeth’s Tlingit mother put her up for adoption. The Wannamaker family took Elizabeth in and raised her in the traditional Tlingit way. She learned Tlingit dances, the Tlingit language and to live off of the land. Her adopted father Andrew Wannamaker, a traveling minister, impressed upon her the importance of public speaking while he preached in both English and Tlingit. Like many indigenous tribes all over the world, the Tlingits preserved their stories and history through speaking, not writing. The Tlingits still deeply value oral history, and being able to speak well is important to them.

Elizabeth grew up in a time when segregation was normal, but attended a non-segregated high school. For much of Elizabeth’s life, signs with messages, such as “No Dogs, No Natives,” were common sights. Her father was a charter member of the Alaska Native Brotherhood, and both parents taught Elizabeth to fight for her rights. Her fight truly took off when she became Grand President of the Alaska Native Sisterhood and her husband, Roy Peratrovich, took on the same role in the Alaska Native Brotherhood. In 1941, Elizabeth and her family moved to Juneau to gain more access to lawmakers. The Peratrovichs always fought against racism, but one of the instances that particularly angered Elizabeth was a usual discriminatory sign at an inn. The US entered WWII that year, and yet the owner of the inn did “not seem to realize that our Native boys are just as willing as the white boys to lay down their lives to protect the freedom that he enjoys.” She and her husband wrote to Governor Ernest Gruening to say that the sign was “an outrage.”

Governor Gruening actively supported the Peratrovichs’ fight for civil rights. With help from territorial representatives, they drafted a bill against discrimination. The bill did not pass, but Elizabeth and her husband refused to give up. She traveled around Alaska preaching about civil rights and even inspired three native Alaskans to run for the Territorial House of Representatives. In 1945, the government re-examined the bill, and the House passed it. The Senate ended up passing the bill too, but not before Elizabeth made her most famous remarks. During the debate, Senator Allen Shattuck asked, “Who are these people, barely out of savagery, who want to associate with us whites with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind us?” When public comment was invited, Elizabeth stood and retorted, “I would not have expected that I, who am barely out of savagery, would have to remind the gentlemen with 5,000 years of recorded civilization behind them of our Bill of Rights.”

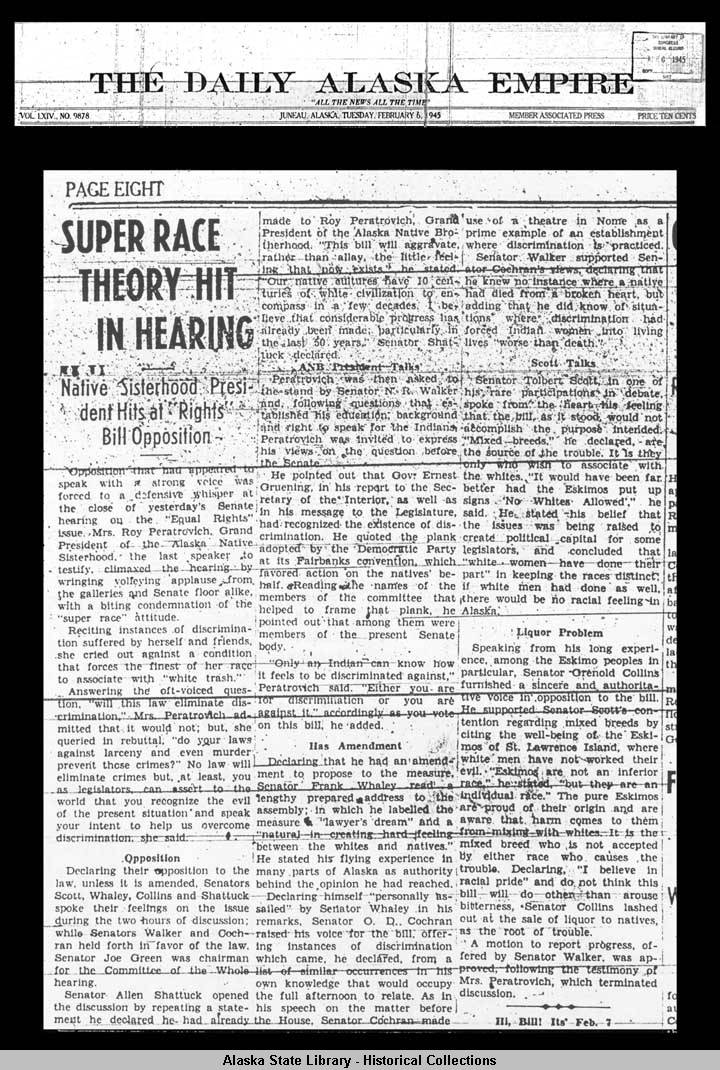

In her following speech to the senators and civilians watching, she explained the racism her family faced throughout the years, from segregated schooling to being turned away from houses for sale when they moved their family to Juneau. Senator Shattuck then asked if she thought the bill would end discrimination against the natives. She in turn asked, “Do your laws against larceny and even murder prevent those crimes? No law will eliminate crimes but at least you as legislators can assert to the world that you recognize the evil of the present situation and speak your intent to help us overcome discrimination.” According to the newspaper article from “The Daily Alaska Empire,” pictured above, her speech was followed by “volleying applause.” Elizabeth’s speech accomplished a remarkable feat for the time, especially as a woman.

Elizabeth lived into the first years of America’s civil rights movement, but died from breast cancer in 1958, just over a month before Alaska became an official state. One of Elizabeth’s three children collaborated on “Fighter in Velvet Gloves,” a book by Annie Boochever about Elizabeth Peratrovich for young teenagers. Multiple places are named in honor of Elizabeth, including a gallery in the Alaska House of Representatives chamber and a park in Anchorage, Alaska. A Google Doodle celebrated Elizabeth in 2020, and the US Mint released one-dollar coins with her likeness the same year. February 16, the day the Anti-Discrimination Act was signed, is “Elizabeth Peratrovich Day.”

Elizabeth Peratrovich is a testimony to the power of words, and proof that hard effort does pay off. Few people outside of Alaska know about her, but Elizabeth is a true inspiration. It is our duty as Americans to remember the people who changed our nation. Elizabeth Peratrovich and her activist family deserve our remembrance, and respect.

"Anna" is a teenage girl who loves to write, read, and do just about anything artsy. She enjoys writing about nature crafts and her experiences while learning to hunt and cook wild game. Anna firmly believes that backyard chickens lay the best eggs and that spending time outside with her flock every morning will start the day off happily. She is extremely grateful to her best friend, who inspired her to really take writing seriously. You can find her lost in her latest idea or listening to her sister "Rose" read book quotes. View all posts by Anna